Christmas Day, 1943

78 years ago today, my father found himself being shot at atop a hill in the South Pacific.

My dad had noticed for some years that I no longer wanted to shoot guns. He had taken note of when we boys in the neighborhood on East Hill Street had stopped playing “war.” I didn’t know much about his time as a Marine in the South Pacific during World War II. The only clues my sisters and I got was when he would name each new dog of ours after battles he was in: Peleliu, Tarawa, etc. In our rickety attic he kept some war souvenirs: a Japanese flag, a sword, and the gun he had taken off a Japanese soldier. One day, without explanation, our father decided he no longer wanted these items in our house. He quietly went and got a shovel out of the garage, gathered together the Japanese spoils of war, and went out to the large weeping willow tree in our backyard. He dug a hole—a very, very deep hole—and buried the gun and the sword and the flag under the shade of that tree. When it was all done and the earth had been restored, he stood there alone, looking down, deep in thought or prayer or who knows what. I watched it all from my bedroom window.

“I want to tell you a story from the war,” he said to me one day when I was thirteen. “I want you to know why every day is precious and why I am thankful each day to be here.”

My dad was one of seven children, and they lived in twelve homes over eighteen years. They moved around a lot, dodging landlords who came to collect the rent they couldn’t afford to pay. The Great Depression had not been particularly kind to the Moore family of Kansas Avenue/Franklin Avenue/Kensington Avenue/Bennett Street/Kentucky Street/Illinois Street/Caldwell Avenue/Jane Street and other depressed thoroughfares on the east side of Flint, Michigan.

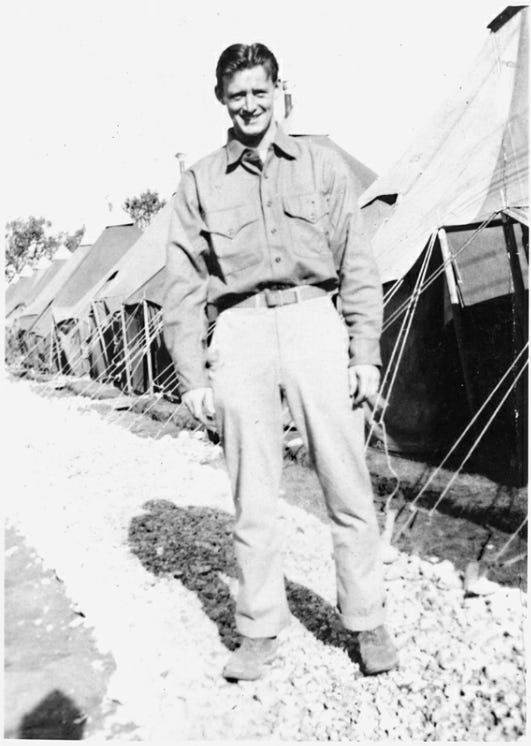

Francis (or Frank, as he was known) was the fourth child of the family, and now, suddenly, at the age of twenty-two, somewhere on the other side of the world, he watched his whole life—falling down the coal chute at two years old, clinging on for dear life at four while stuck on the running board of his dad’s moving car, the day when he was ten and his mother was forced by the sheer weight of their abject poverty to gather Frank and his brother Lornie and take them to the orphanage in Flint because she simply couldn’t afford to take care of seven children, getting cut from the high school basketball team the day before the state championship so that the coach could make room for a younger player coming up next year, getting fired the first day of driving the Coca-Cola delivery truck because he told his boss he “didn’t much like the taste of Coke”—ALL of this flashed before him as he lay exposed on top of Hill 250 on some island in the South Pacific, watching as the tracer rounds were fired from the plane above, firing directly at him and his fellow Marines on Christmas Day, 1943.

Except the planes, like him, were American.

How Frank came to find himself on Hill 250 on the island of New Britain made about as much sense to him as the fact that his own side was now trying to kill him with such ease. What led Frank here was a worldwide war that was about something much bigger than his small world in Flint. His world was one of factory work and sports and Saturday nights at Flint’s Knickerbocker Dance Hall. Though they lived the shared poverty of many in the worst days of the Great Depression, the Moore brothers—Bill, Frank, Lornie, and Herbie—each took extra care to always have a clean, well-pressed suit, a sharp haircut, and enough coin in their pockets to get into the Saturday night dance.

They even took dance lessons upon leaving high school because the older boys had told them it was “a good way to meet girls.” So they all became good dancers.

But this soon came to an end on the morning of December 7, 1941. Pearl Harbor was attacked and my father and his three brothers all enlisted to go fight fascists and protect our Democracy. Yes, I know what you’re thinking—some things never change.

“Private Moore,” the sergeant whispered. “Cap’n wants ya.”

It was sometime around 11:00 p.m. on Christmas Eve, 1943. Frank Moore wasn’t sure if it even was Christmas Eve, or Christmas Day, and he didn’t care much for this thing called the International Date Line that meant he was always a day ahead of his life, the life he left back home. Instead of trying to do the math, he just decided to keep himself on “Flint time.” Easier. Friendlier.

He and a thousand other Marines had bunked down early on this night on the transport ship as it headed toward the coming battle on New Britain, an island that was part of Papua New Guinea, a few hundred miles off the north coast of Australia. There wasn’t much Christmas celebrating going on, though there were, no doubt, many, many prayers being said. Because at 0700 hours they would be loaded into amphibious assault vehicles and lowered into the Pacific Ocean just a mile off the coast of Cape Gloucester, New Britain. But for now, Captain Moyer wanted to see my dad.

“I hear you can type,” Moyer said to the young private.

“Yes, sir, sorta,” replied Frank, not quite understanding what typing had to do with killing Japanese or Christmas.

“I want you to stay behind here on the ship,” Moyer said. “I need someone who can type up the casualty reports.”

“But sir…”

“Listen, this is important. We need to be accurate and we need to be accountable. If not to HQ, at least to the families of these men.”

My dad got it. He was being offered a free Get-Out-of-Dying card. Stay behind on the boat and type. Don’t die in the wave of bullets and mortars that will spray across the chests and the necks and the heads of his friends and fellow Marines. Live for another day.

But this had already happened once before when a previous captain who had also leaned my dad could type ordered him to stay behind to type up the casualty list. He did as he was told and none of the troops in his unit that went out on patrol that day came back alive. He was the only one of them still living, simply because he could type. For the better part of that night and into the next day he typed up the information of every one of his lost friends. It would be weeks before he could snap out of it and he had no choice but to snap out of it because the battles of the South Pacific were a slaughterhouse. He wondered if he had joined the Army instead of the Marines perhaps he’d be somewhere in the Mediterranean right now. Surely that had to have been better.

The offer from Captain Moyer to stay behind and type seemed mighty tempting, but Frank knew that staying behind on the ship was only delaying the inevitable. If your time is up, you might as well go on Christ’s birthday.

“Captain, I’d rather stay with my battalion. If it’s OK with you, sir, let me stay with my buddies. And to tell you the truth, my typing stinks.”

“OK,” he told the private, “you’re dismissed. Get some sleep.”

“Thank you, sir.”

Frank returned to his bunk, and for the first time in a long time, he had no problem falling asleep.

At 0500 hours the booming sounds of the artillery guns from the nearby American destroyers made Frank stop and wonder if he had made a mistake turning the captain down. Someone mentioned that Moyer and a reconnaissance party had slipped down into the bay two hours earlier with the intent of landing before the invasion, under cover of darkness, in order to find out just what the First Marine Division was about to face.

Soon my father was crammed tightly into an amphibious lander with fifty or so other Marines heading toward the Japanese-held beach. He said one final prayer before the door came down and deposited everyone into the slosh of chest-high saltwater. The first thing Frank noticed was that it was nearly impossible to walk, impossible to fire his gun. His focus was on some very short-term goals: one foot forward, now the other foot. Keep gun above head so it doesn’t get wet. Now one more foot forward. This seemed like it took an hour or more (it took less than five minutes), and Frank kept wondering how it was that he was still alive. Dumbroski, a sergeant who had been the big, tough bully of the unit until this moment, was frozen in place, weeping. Keep moving. Leg. Foot. Rifle. Dry.

And then suddenly my dad was on the beach. A beach of black volcanic sand. Red blood on black sand made for an odd mixture; both caught the light of the morning sun and glistened with more life than such a scene deserved. The brush of the jungle was just a few yards away and appeared to offer the best chance for cover from the incoming shells being fired from a cliff about a half-mile away. Within a couple hours most of the Marines had landed and the casualties were not as great as anticipated. The Japanese had decided not to fight this battle on the beach in the hopes of drawing the Marines further inland to meet their doom.

Frank’s battalion moved out on the left flank to head toward higher ground, while other battalions pushed straight through the jungle. Frank and his men were again surprised at the absence of Japanese gunfire or resistance. Within the hour, moving fast, they began to climb Hill 250. It seemed too easy.

They were right.

For some reason they had found a magical crack in their own American front line and, without realizing it, slipped right through it with no one noticing. They were now, unbeknownst to themselves, in Japanese territory, a good thousand yards ahead of what everyone believed were the front lines of the United States Marine Corps.

Their map indicated they might be on Hill 250. It is generally believed that during a battle, it is better to be on top of the hill than at the bottom. You don’t need to be a West Point graduate to understand that. So Frank and the others began to make their way up the hill. The Japanese at the top of the hill didn’t want any company that day, so they lobbed everything they had on this lost battalion. Then, out of nowhere, a monsoon rain erupted, making it impossible to see more than a few yards ahead. That gave the Marines the cover and the advantage they needed, and they quickly made their way up Hill 250. With grenades, 37mm machine guns, and sheer force of will, they took the hill. The Japanese on top of the hill had no way of knowing that this was just a small unit of Marines; they assumed that they were facing an invading horde of hundreds, if not thousands, of Americans. So they retreated down the other side, where the larger force of their Japanese army lay in wait.

As the Marines secured the ridge at the top, the rain stopped. This first victory felt good—not exactly flag-planting good (they had barely advanced onto the three-hundred-mile-long island) but good enough—and there were remarkably no casualties.

It was then they heard the sound of airplanes. This was a welcome sound, as it was the sweet hum of a Wright Cyclone engine on an American B-25, the sound that said, Here we are, boys! The Cavalry to the rescue! These grunts on the ground had cleared this hill—and now it was time for the flyboys to swoop in and take out the valley!

But as Frank squinted at the planes backlit against the now-punishing tropical sun, he saw a plume of smoke coming out of one of them. The plane had been hit. How could that be? These fighter planes were coming from behind them, coming from American-held territory—who then would have shot at an American plane from back there?

In fact, it was Americans back on the beachhead who had actually fired on the American planes, thinking (wrongly) that they were Japanese bombers. The American planes, in turn, thought that the Japanese had hit them (two of the B-25s went down in flames), and so when they looked down on Hill 250 and saw the “Japanese” whom they thought fired on them, well, now it was payback time.

But, of course, these were not Japanese on Hill 250; these were the men of my dad’s unit. Swooping in at what seemed like a hundred yards above treetop level, the B-25s strafed Hill 250 with their mass of bullets. Frank and the men had no time to signal not to shoot. We are on the same side! There was nowhere to run for cover. They threw themselves down and prayed for the best. Frank could see the tracer rounds coming from the planes straight at them. He accepted that this was the end of his life, and he closed his eyes as that life, with all of those scenes of joy and struggle and family, sped by him in an instant. He knew that the next instant would be his last.

When Frank opened his eyes, his life was not over. But the scene in front of him was one he had never wanted to see. Lying beside him was one of his friends. His face was gone. Frank looked up and over this deceased Marine to see a dozen or so of the men in his unit lying there, riddled with bullets, many crying out for help, some alive, some surely dead, their uniforms beginning to stain broadly with the blood that was oozing out of their numerous wounds. In all, fourteen Marines were hit and one was dead. Only Frank was alive and untouched. For a moment he was convinced that he must be dead, too, as it was simply not possible to survive that many bullets fired from so low, bullets that not only penetrated the bodies of all of his buddies but also chewed up the volcanic rock all around him. How could this be? Why was he untouched? And why in God’s name did this good Marine next to him die at the hands of other Americans?

My dad had little memory of what happened next. Apparently the Marines on the front lines behind him had witnessed the whole stunning incident. They reached Frank and the others as Frank was trying to administer first aid to the other marines. Medics and stretchers were called in, and after the wounded were attended to, Frank was brought back down the hill to the staging point closer to the shore.

“I’m OK,” Frank said after a few hours of rest. “I’m ready to go back.”

“It’ll be night soon,” a corporal told him. “I think it’s OK if you stay here with us.”

He thought perhaps someone would want to talk to him, to file a report or something. But there was a war, a real war, going on, and after he asked one lieutenant why this tragic mistake had happened, he was told this happens in war all the time. “You just have to move on and win.” After that, my father never asked about it again.

The following day, he got word that Captain Moyer and the men near him had all been killed on that recon mission. He could see that this was the way it was going to be. Death, then more death. Soon another captain from the front line appeared with two privates who had “cracked” under duress.

“These guys are my wiremen,” he told the officer in charge. “They’re no good to me now. Trade me these for one of your guys.”

The lieutenant looked at Frank.

“This guy’s a machine gunner. I’ll trade you him.”

“Don’t need a gunner, need a wireman. Someone who can carry big spools of radio wire, run fast, and duck.”

“This guy knows how to duck,” the lieutenant responded with a wry tone. “Believe me.”

“A wireman?” Frank asked. “Carry and run the radio wire from the front lines back to the command post?”

“Yup.”

“No more firing a gun?”

“Nope. You can’t fire a gun and roll out a big spool of wire at the same time. But the enemy will fire at you. They go after the radio wire guys first so that we’ll be unable to talk to HQ. You take this job, you better have some guts and know some fancy dance moves to dodge those bastards.”

Guts? Dance moves? Why didn’t he say that in the first place?

“I was a wireman for the rest of the war,” my dad said as he finished his story. “I would never fire a machine gun again. I would be shot at over and over, but I couldn’t shoot back because I had to carry the spool of wire. It was kind of crazy it all worked out that way.”

I thanked my dad for telling me all of this, but I was thirteen and, by the end of it, I was fidgeting around and checking the clock. I wanted to go outside and hang out with the other boys. My dad noticed none of that, as his mind was clearly still back in 1943.

“Every Christmas I think about that day. That I got to live, somehow… lucky, I guess…” he said, his voice trailing off.

“Dad, um, can I go, now? Maybe you can tell me another war story later?”

It would be years before I heard one again.

Now, on this Christmas Day, like the many before it, and certainly on each Christmas Day since my father passed away in 2014 at the age of ninety-three, I have heeded his words to savor each day, to never take for granted this precious life. As I sit here this morning on Christmas 2021, I find myself living alone during a global pandemic, lucky to not be amongst the dead or the infirm and realizing that is because I’ve done what science and medicine and my own common sense have told me to do. I have kept my physical distance from nearly everyone, learned of friends who didn’t make it, a deepening loneliness enveloping me, trying not to think what I know to be true and trying not to say it aloud as to when I believe this madness will be over. We all know it isn’t soon. But we reach for hope any chance we get. We move forward. We fight to see another day. In this apartment, by myself, I record my podcasts in one room, and write my weekly letter to you in another. In between I read books, I stay in touch with family and friends, I watch Jeopardy and Sports Center and the Christmas rain outside my window right now, knowing that the snow that should be there, the snow that was always there around Christmas, like my parents, always there, now gone, their gift of life to me still treasured and their son promising to use their gift and join with others to find a way off this hill.

A happy holiday to you all. My gratitude to you is immense. Our fight against Coup and Climate and Covid shall, against all odds, succeed with our fearlessness and smarts and love that resides in every single one of us.

Thank you Michael. The perfect story for today. I was six in the London Blitz, was bombed, machine gunned in the streets and looked after by my mother, the gentlest soul and father a fire fighter. How they lived through this is hard to imagine but nazi-ism almost won. It was stopped by amazing courage from millions. How can we wake the stupefied public to the fascist danger from republicans today.

Thank you, Michael, for the gift of this story. Many of us in my circle of friends entering the last third of our expected life spans have been contemplating what it means to be elders in this time, culture, and place. Your story is so instructive--for what your father shared with you, for your developmentally-appropriate response at the time, and for the great blank spaces of what may never have been shared. Thank you for all of it, and for the implicit encouragement to take that space, to tell our stories, to create the active and creative moments to put our collective instructive experience to work for change that our younger inhabitants of our planet need from us. How courageous your father was to finally share that horrific and painful story with you, and how courageous you are to carry his story forward. My deepest gratitude to you both.